For the Common Defense

28 February 2020

Paul J. Springer

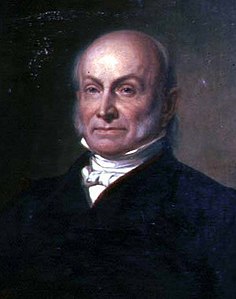

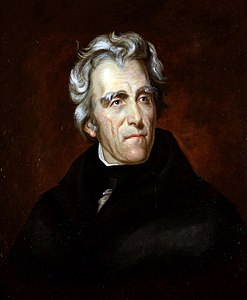

In 1824 the populist candidate Andrew Jackson won the largest number of both electoral and popular votes - and lost the election to the John Quincy Adams, the establishment candidate, in the House of Representatives.

Contentious elections are not a new concept in the United States, and it should not be a surprise that the Democratic Party is engaged in a factional struggle to determine their candidate for the presidential campaign. As is so often the case when a party is selecting a candidate to run against an incumbent, the primary uniting factor within the party is a desire to oust the current office-holder. Sometimes, the incumbent looks almost unbeatable—in which case the party tends to select an opponent to go through the motions of a campaign with little hope of victory. That candidate is often considered a “moderate” within the party, one who has devoted decades of service to the party, with the reward of running a doomed campaign. But, when the incumbent seems vulnerable, more competitors come out to vie for the office, and the nominating contests can turn ugly. We tend to assume this is a modern phenomenon, but in reality, it has been present since the beginning of the republic.

There are often complaints about the existence of the Electoral College, and proposals for how it might be “fixed” or replaced. However, getting enough popular support to radically alter the electoral system, which would by definition require a Constitutional amendment, is extremely far-fetched. Thus, candidates for the office of the presidency should expect to compete within the established rules of the contest. For all intents, those rules have been in place since the ratification of the Twelfth Amendment in 1804. Effectively, each state can utilize its own methods to choose the electors it sends to the Electoral College. Those electors vote for a candidate for the presidency and the vice-presidency, and the winner of each election is declared if one of the candidates has a majority of the votes.

In 1824, the United States was in an economic boom, at peace with its neighbors, and in general tended toward political harmony. Its departing president, James Monroe, had served two terms, and in 1820, had actually run for reelection without opposition. The Federalist Party assumed he would win against any candidate they could name, so they just did not bother to name one at all. Not surprisingly, Monroe won handily, although the final tally was not unanimous. In the popular vote, the Federalists garnered 16 percent of the vote, despite not actually having a candidate, and DeWitt Clinton (who was a Democratic-Republican, like Monroe), won just short of 2 percent of the popular votes. In the Electoral College, Monroe earned 228 votes. 3 votes were not cast, and one electoral voter, William Plumer of New Hampshire, voted for Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. Given this level of unity within the nation, it came as quite a shock when the 1824 election became one of the most contentious in history.

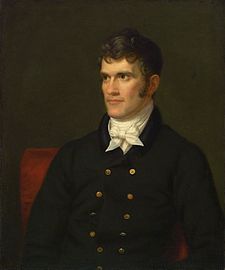

The first signs of factionalism within the Democratic-Republican Party came during the nominating season. As Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams was effectively the “heir apparent” to the presidency, as both Monroe and James Madison had held that role prior to being elected president. But, when the Congressional caucus met, it selected Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford as the party’s “official” nominee. Many party leaders denounced the use of a Congressional selection system as being undemocratic, and in addition to Crawford, Senator Andrew Jackson, Secretary Adams, and Speaker of the House Henry Clay all openly sought the office. Jackson was a war hero from the War of 1812 and subsequent campaigns against Native American tribes in the southeast. Born in Tennessee, he could count upon the broadest regional support of the candidates. Adams was the son of former president John Adams, and had a base of support in New England, the most densely-populated region in the young nation. Clay, a young Congressman from Kentucky, had built a powerful system of political alliances to earn his legislative role, and hoped to leverage those connections to seek the higher office.

The election ran from the end of October until December 1, when electoral votes were opened and ballots counted. None of the candidates garnered the 131 votes needed to win the office outright, with Jackson coming closest at 99, and Adams in second with 84. Crawford and Clay were a distant third and fourth, with 41 and 37 votes respectively. Jackson had also won the largest number of popular votes, collecting just over 41 percent of those cast—but the victor could only be named through the existing electoral process. The race for the vice-presidency was quickly decided—John C. Calhoun handily won that office with 182 electoral votes, having been the only serious contender for the role.

With the presidential victory in doubt, the members of the Electoral College turned to the Constitution for guidance. According to the Twelfth Amendment, the selection of the presidency now fell to the House of Representatives, where each state’s delegation would cast a single vote on behalf of their state, with the candidate who received the most state votes declared the winner. According to the Amendment, only the top three finishers from the original contest were eligible, meaning that Henry Clay was dropped from contention—but as the sitting Speaker of the House, he was thus in a key position to influence the final outcome. Clay approached various state delegations and began working to block Jackson from winning the presidency. Despite being from the same region, Clay loathed Jackson, found him utterly unqualified for the office, and believed he would be a disastrous choice. Thus, he worked to convince the delegations in states where he had polled well as a candidate to throw their support to Adams. Jackson and his supporters assumed that the process would select him, on the basis of his broad regional support and his earning the highest number of popular and electoral votes—and he was wrong. Clay’s machinations worked, Adams received the support of 13 states (to Jackson’s 7 and Crawford’s 4), and was named the sixth president of the United States.

The election of 1824 was a bizarre one, to be sure—it was the only time that the legislature has ever been called upon to decide the outcome under the parameters of the Twelfth Amendment. But the aftermath of the election was, in many ways, even more odd, and set the stage for a radical revolution in American politics. Jackson’s supporters immediately decried the results, claiming that Jackson had been cheated of an office he rightfully won. They accused Clay of selling the office to Adams through a “corrupt bargain,” in which Adams gained the presidency in exchange for naming Clay as his Secretary of State. These charges were magnified when Adams did name Clay to that role, effectively making him the heir apparent to the office.

Whereas previous presidential campaigns had been relatively short and low-key affairs, with the candidates named in the late summer or early autumn, and the results delivered by the end of the year, Jackson and his supporters commenced a campaign for the presidency in early 1825 that lasted until the 1828 election. Not only did they campaign for the office, they undermined all of Adams’s efforts to govern effectively, and worked at the state level to change how electors were selected in presidential elections. In 1824, six states still left the selection of Electoral College members to the state legislatures. By 1828, that number had dropped to only two. Virtually every state opened voting to all white adult males, dropping any previous property qualifications or other expectations.

In the rematch, Jackson was the candidate of a newly-emergent Democratic Party while Adams ran as a member of the National Republican Party. (Despite the similarities in title, neither of those parties should be considered the same as the modern political parties.) Adams had the same base of political support in their second contest—New England and a small amount of the mid-Atlantic states. Jackson, on the other hand, expanded his base to encompass all of the South, West, and most of the mid-Atlantic—meaning all of the regions that were experiencing substantial population growth went to Jackson. In the electoral college, he captured more than two-thirds of the vote, bringing a mandate with him into the office that allowed him to enact a far-reaching platform that significantly transformed the American political landscape, and instituted a period commonly referred to as “Jacksonian Democracy.” His vice president, strangely enough, was John C. Calhoun, who had won reelection in a landslide.

In the modern era, we have a tendency to assume that we are confronting “unprecedented” political situations, or that our level of rancor and vitriol is somehow unique—but a careful examination of past contests reveals, if anything, we have become more civilized in our ability to conduct elections and live with the results. Unfortunately, it is all but guaranteed that regardless of which candidate secures victory in November, the losing party will commence a campaign to undermine and short-circuit the administration. And, of course, the election of 2024 will begin on Wednesday, November 4, 2020—all thanks to the Jackson partisans of nearly 200 years before.

Comentários